by Liza Tripp and Denise Jacobs

After a typical translator’s day working on dense annual reports and ponderous litigation files, fashion translation seems fun enough. What better diversion than immersing yourself in skirts and dresses?

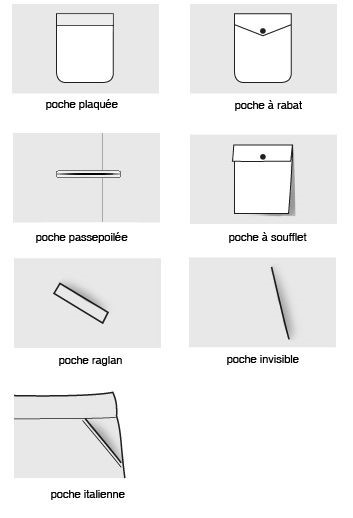

Yet as with all well-executed translation, challenges abound. Sewing terms are technical, precise, and sometimes mysterious. There are endless variations of pleats, pockets, darts, seams, necklines, sleeves, hooks, buttonholes, and lapels. Fabric finishes also vary widely depending on textile manufacturers and whether the items are intended for haute couture or the mass market. Fashion is visual, yet translators are often faced with descriptions of pieces that have no accompanying images.

French terms for a variety of pocket styles.

Photo credit: link

English terms for a variety of pocket styles.

Photo credit: Pinterest

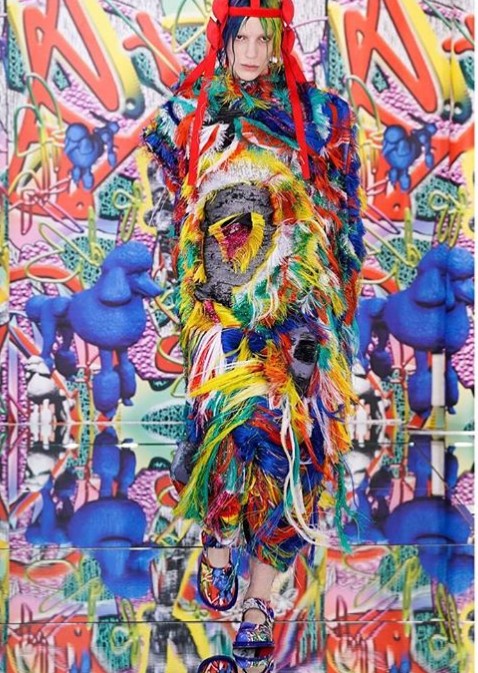

Haute couture and visionary designers often reference historical clothing styles and techniques in their creations. Max Mara even maintains a private historical fashion archive, which serves as a resource for its designers: “Fashion is a culture. Designers don’t create alone,” noted the brand’s creative designer.[i] Sometimes designs make literal references to historical items, in which case translations are best served doing the same. Indeed “les paniers” on a Junya Watanabe dress with zippered duffels at either hip are a fairly literal interpretation of the historical “panniers.”

Photo Credit: 1stdibs

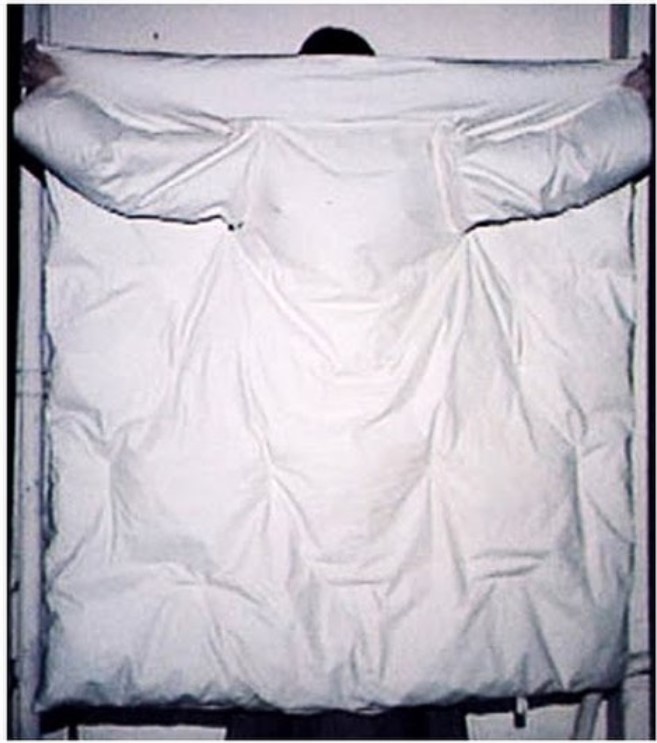

In other cases, historical fashions serve to spur the designer’s creativity in developing entirely new and avant-garde concepts. Consider Margiela’s use of “blouse blanche,” not a blouse at all, but a white lab coat, pointing to the highly skilled French “petites mains” who worked in haute couture ateliers.

Photo credit: Instagram

The fashion house uses the historical term and the piece itself as a jumping off point for a multitude of items in its collections. These designs have included everything from all white clothing (some of them blouses!) to head-to-toe white down comforters worn as coats, right down to the plain white labels inserted in all of its pieces. Indeed, in Margiela’s case, the historical “blouse blanche” has become a way of branding the house itself—simple, exceedingly modern, but deeply connected to the past.

Photo credit: Instagram

To complicate matters further, some terms are “one-offs,” where sometimes a more literal translation is warranted. Pierre Cardin once devised a pair of pantalons à roulettes, or roller pants, with a leg finishing in a roller-skate wheel shape. Recently, there was a description for an “inside-out poodle jacquard” in a review of John Galliano’s latest collection for Maison Margiela, which turned out to be exactly as described.

© 1971. Image used with the permission of Jean-Pascal Hesse.

Photo credit: Instagram

While having a photograph of the garment or accessory is, of course, the ultimate resource, translators are often left in the dark. Technical and fashion dictionaries can be helpful starting points. From there, we have turned to designers’ websites, online videos of fashion shows (time consuming, but elucidating), reliable fashion reviews (Vogue, WWD, New York Times, BoF), blogs and sewing websites found online, as well as museum and auction house catalogues. Reaching out to fashion houses or museums is also an option, time permitting. We were delighted when a museum in Paris even sent us photographs of the back of a garment we simply could not envision for a book translation.

As always, it is essential to conduct online research meticulously, with context, linguistic register, and final audience in mind. When in doubt, we recommend relying heavily on description, so your reader can see the item in question in their mind’s eye. Sometimes leaving a term in French can be an option, a way of naming the object where you otherwise could not. Obviously, this technique should be used judiciously and thoughtfully.

Yet, perhaps due to French’s longstanding role as the lingua franca of fashion, use of French in English is sometimes de rigueur. Indeed, when translating historical books on classic couture or biographies of legendary houses or couturiers, publishers and editors even mandate that certain words should be kept in French. haute couture, atelier, petites mains, flou and tailleur are a few examples.

Nevertheless, as can be expected in fashion, change is always in the air. English suddenly abounds in French, and very much so in fashion reporting. Sometimes the terms are simply borrowed (la fashion week, les shows, le vintage, le it bag) but words cannot always be handily back-translated into English. The word “oversize” in French, for example, often equates not to our English-language conception of oversize, but to descriptions like “roomy,” “relaxed,” or “slouchy.” Perhaps translating fashion texts is so tricky because fashion itself is a language. Miuccia Prada herself has said, “What you wear is how you present yourself to the world, especially today, when human contacts are so quick. Fashion is instant language.”[ii] As translators, we present texts that can be read and absorbed in a moment. Yet how we present that language should be a detailed process using mixed research sources and a bevy of translation techniques and styles.

[i] Olsen, Kerry. “In Max Mara’s Archive, Decades of Italian History.” New York Times, September 19, 2018, link.

[ii] Galloni, Alessandra. “Interview: Fashion is how you Present Yourself to the World.” Wall Street Journal. Updated January 18, 2007, link.

Liza Tripp has been a translator of French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese into English for over 15 years. Much of her French and Italian work is in the luxury fashion sector. She most recently translated Martin Margiela: 1989–2009 with Denise Jacobs, which was published by Rizzoli in conjunction with a show at the Palais Galliera in Paris. She holds a BA in French translation from Barnard College, an M.Phil. from the Graduate School and University Center of the City of New York, and a French to English Certificate in Translation from NYU SCPS.

Website: www.lizatripp.com

Denise Jacobs is a French to English translator focusing on illustrated books about fashion, jewelry, art, travel, and the French lifestyle. She has an MA and M.Phil. in French literature from Columbia University. In addition to publishing more than 40 books, she has also translated several biographies, documentaries, and television news program segments. Website: www.deniserjacobs.com