By Paula Arturo

I. The Case for Methodology

Although translation is one of the intellectual professions par excellence, translators often lack methodology, meaning that many translators approach translation by simply transferring from L1 to L2 with perhaps slightly more thought to nuance than a machine but far less thought than often required by context. This is, at least in part, a reflection of two serious issues in the language profession: i. lack of entry barriers to translation as a profession; and ii. an obvious deficit in translation education (both of which exceed the scope of this post).

Even without methodology, many professionals can still render exceptionally well-written and accurate target texts. But even those who put the “pro” in professional sometimes struggle to explain their linguistic choices and could probably benefit from a thought-out and methodological approach to translation—one that can triumphantly withstand even the most rigorous scrutiny. And, in times when the contractual relationships to which many translators are bound often condition payment to such scrutiny, being able to justify one’s linguistics decisions is more important than ever.

Additionally, and perhaps more importantly, a methodological approach to translation has significant metatheoretical value because it can infuse translation practice with a solid theoretical foundation for understanding what it is that we do when we translate. This foundation can help us inform our own linguistic decisions and provide a solid framework for interpreting source meaning and conveying the message naturally in the target text, without sacrificing fidelity to source in the process or diminishing the overall message by resorting to literality.

So, whether we do it out of love for solving linguistic puzzles or practical down-to-earth reasons like ensuring we get paid, there are good reasons to adopt a methodological approach to translation. And in this article, I will use contract translation to exemplify how translators can develop such an approach.

But before I get into it, I’d like to make one important clarification: in a different series of posts on plain language and translation (Arturo 2018), I argued that, regardless of whether or not we write the target text in plain language, translators can still benefit from applying plain meaning interpretation to the source text, the way judges do in court, to better capture the message that needs to be conveyed. To do so, I postulate that translators need to familiarize themselves with interpretation theory in general, and textualism in particular. The reason I bring this up now is because the model I will develop in this article parts from that same premise: the translator’s goal should always be to extract the plain meaning of the source text to adequately understand the message that needs to be conveyed, regardless of how well or poorly the source text was written.

I am aware that each legal document is a world in itself and will pose particular challenges that the translator will have to overcome. But because contract translation is what puts food on many translators’ tables, I’ll use contract translation to walk readers through this sample methodological approach—which happens to be the approach I use for contract translation. Doing so serves two main goals: i. to exemplify how it can be done; and ii. to provide a framework that each reader than can later adapt to their own language combinations, contexts, and needs.

In other words, I’ll give you the theory and show you how it can be applied in practice. The rest, dear reader, is up to you.

II. Demystifying Contract Translation

There are two common misconceptions in contract translation: i. that contracts are drafted vaguely on purpose; and ii. that, when in doubt, fidelity to source demands literality. Nothing could be further from the truth.

No self-respecting lawyer wants the courts to breathe meaning into their contracts. A poorly drafted or vague contract can cost our clients millions of dollars in litigation. So, the last thing we want, as primary drafters, is to leave anything open to interpretation. Translators, in turn, need to understand the practical consequences of that in translation.

First, when the source text is vague, it’s always a good idea to flag that vagueness and ask the primary drafter for clarification. Second, once source is clarified, there can be no vagueness in the target text. This places a particular burden on translators to thoroughly understand the source text and render a clear and pristine translation. And that will never require literality. Literal word-for-word translations result in target texts that may be “faithful” (if we define fidelity in the poorest of terms), but are ineffective and even nonsensical in the target language.

So, the translator’s goal when working with contracts is to first understand what the parties are trying to achieve in each and every clause (i.e. to identify the purpose of the clause) and second to make any necessary adjustments to the target text to make sure that purpose is adequately conveyed in the target language.

III. Three Key Questions

Understanding any contract clause and translating it correctly means being able to answer three key questions.

1) What are the parties trying to achieve with this clause?

2) What category of language does that place us in?

3) What characterizes that category from a purely linguistic point of view?

Question 3 will not only help us adequately phrase the clause in the target language, but also help us interpret it correctly, even if it is poorly drafted in the source text. In other words, while you may never come across a contract that actually respects any of the linguistic rules that characterize (or should characterize) the relevant category of language, looking past the flaws in the source text and interpreting it as if it had been written correctly will help you transfer it accurately and naturally into the target language.

IV. The “How”

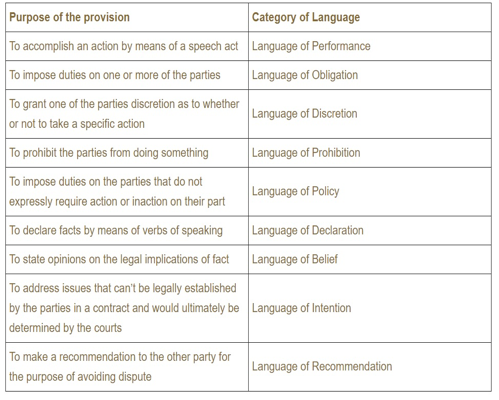

Because I personally follow Ken Adams’ categories of language when translating contracts (Adams 2013), I will base this article on his categories. But you don’t have to follow these particular categories; what I’m proposing here is a method, and methods can be adapted to our subjective preferences. You can apply this method to any category of language, even if you’ve invented your own categories, because that’s the beauty of having a method in the first place!

To apply the method, you’ll need to remember our three key questions. And with those questions in mind, let’s look at the following example:

Contract Title: Sale and Purchase Agreement

Problem Clause: Subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein, Acme shall sell to Wile E. Coyote and Wile E. Coyote shall purchase from Acme, all of the Assets, free and clear of any Lien other than Permitted Liens.

The Issue: The use of shall in shall sell and shall purchase is obviously “off.” But why is this a problem in translation? Because shall is often used by lawyers to indicate both future tense and obligation—despite solid advice to the contrary (Arturo, Translating Lawyers 2018).

So, the first thing we need to determine is what the parties are trying to accomplish: Are they selling and purchasing now or on a future date? Willingly or conditionally? Are there any additional steps required or are they buying and selling by means of the speech act of saying “I’m selling/I’m buying”?

Reasoning it out: We know this is a sale and purchase agreement. Therefore, we also know that the contract itself is intended to make that sale and purchase possible, which is merely another way of saying that the parties want to perform the sale and purchase by means of this contract. So, now that we know what they want to do, then we know what category of language we’re in.

The category, again following Adams, is Language of Performance. It’s the language we use when we want the mere statement of something to have legal effect. And now that we know what category of language we’re in, if we’re familiar with the linguistic traits of that category, we can figure out how to interpret the clause, regardless of whether or not the primary drafter followed the rules for that category.

What the parties meant: Once we’ve identified the parties’ intention, category of language that intention belongs to, and main features of that category, we are ready to interpret the clause not on its literal word-for-word phrasing, but its intended meaning. If we read the clause as if it had been written as follows…

Subject to the terms and conditions set forth herein, Acme hereby sells to Wile E. Coyote and Wile E. Coyote hereby purchases from Acme, all of the Assets, free and clear of any Lien other than Permitted Liens.

…And we translate that intended meaning accordingly, we’ve respected fidelity to source without letting literality hinder our translation. In other words, we will have interpreted the clause correctly (in its plain meaning interpretation) and are in a better position to translate it accurately and naturally into our target language.

The rest is just repetition. If we summed up all that theory into four simple steps, it would look something like this:

Step 1: Start with your first key question: What are the parties trying to achieve with this clause?

Step 2: Once you’ve identified what the parties intended, ask yourself what category of language that falls into.

Step 3: Once you’ve identified the right category of language, rephrase source accordingly.

Step 4: Translate. Smile. Congratulate yourself for a job well done. Repeat.

V. The Tools

The good news is this method is heavily reliant on cheat sheets, and once you’ve developed those cheat sheets it’s an easy and straight-forward method to use. The bad news is those cheat sheets are not easy to develop. You’re going to need to hit the books… hard.

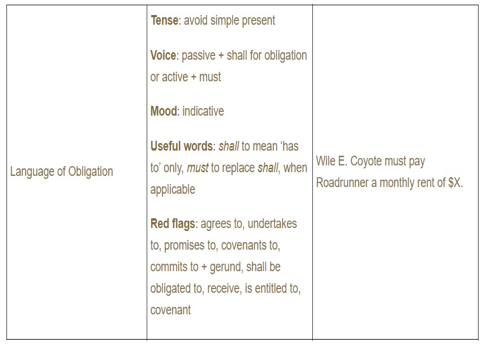

To help you get started, here’s an example of some of the cheat sheets I use for contract translation:

V.1. Category per Contract Clause Purpose

V.2. (Sample) Category Characteristics

VI. The Takeaway

In this article, you’ve been given the what, the how, and the tools you’ll need to develop a methodological approach of your own. Provided you put in the work, this method can be extrapolated to any area of legal translation and adapted to any language combination. So, the rest is up to you.

VII. References

Adams, Kenneth A. 2013. Manual of Style for Contract Drafting. Chicago: American Bar Association.

Arturo, Paula. 2018. Translating Lawyers. November 7. Accessed November 9, 2018. https://translatinglawyers.com/2018/11/07/legal-translation-and-plain-language-part-1-what-translators-can-learn-from-judges/.

—. 2018. Translating Lawyers. October 31. Accessed November 24, 2018. https://translatinglawyers.com/2018/10/31/the-shall-conundrum-when-use-becomes-abuse-2/.

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

About the Author

Paula Arturo is a lawyer-linguist and Professor of Law. Throughout her 20-year career, she has translated the works of six Nobel Prize laureates and high profile authors from Yale Law School, NYU, and the University of Buenos Aires, among others. As an independent lawyer-linguist, she translates shadow reports for the United Nations Universal Periodic Review of several Latin American States, helping non-profit and grassroots organizations have a voice before the Human Rights Council. Through her online legal writing and translation academy, she helps legal and linguistic professionals alike to hone their skills and get their messages across accurately. Committed to the professionalization of translation and interpretation, she serves her professional community as administrator of the American Translators Association’s Law Division and co-head of legal affairs at the International Association of Professional Translators and Interpreters.

Well said.

To reiterate it in a few words.

Agreement is when two parties actually negotiate the terms and provisions. E,g in German = Vereinbarung.

Contract can be the end product of the agreements reached, but may also be the stipulationlations made by one party to have them agreed to by the other party, or, more often than not, be a demanded, command, request to be signed by the other party as agreement to obtain something. In German = Vertrag.

I am a new ATA member. Your piece was well written and I enjoyed it. It gave me some food for thought. I have only one comment regarding the

fidelity/transparency issue.

I mainly translate legal material from Flemish to Hebrew. Part

of the documents I translate, are for litigation purposes (as

opposed to contracts). From time to time I encounter sentences

and phrases, where some kind of literal translation is

required. The phrase should have said X but it says Y and Y is

open for different interpretation (which could be used in

litigation). Even if I translate the phrase as intended (X), I

feel I should at least add Y between brackets.

Looking forward to reading many more articles like yours!

WOW! Thank you, Paula, for this breakdown. I have always done so by default, now I see I have a “method.” Abraços.

Hi Paula,

Thank you for this insightful and actionable post.

Best regards,

Heike

Thank you Paula, I totally agree a translation method can help produce amazing results. I wrote my own general translation methodology (see https://longtontranslation.com/publications/) in 2017. It may not fit all translators’ needs but can help you find your own method to produce consistent quality results.

Anybody interested in collaborating to produce a French cheat sheet of categories of languages that we could circulate in the ATA Law Division? I started mine a year ago, but would love doing more brainstorming about it.