(images published with the speaker’s permission)

At this year’s ATA conference, the Science & Technology Division had the honor of welcoming its Distinguished Speaker, Scott L. Montgomery, who presented a thought-provoking session on English and Translation in the Era of Globalized Science.

Scott opened and closed his talk with the same stunning image of a lake in the Rocky Mountains. Multiple streams flow into it from all sides, feeding a shared body of water. For him, he explained, this is the perfect metaphor for modern science: the streams are national and local scientific traditions, each with their own languages and cultures, while the lake is the lingua franca where this knowledge gathers, mixes, and becomes more widely accessible.

As we will find out later during this talk, water doesn’t just flow in: it also flows out again as streams, nourishing the surrounding landscape. In the same way, ideas that enter the lingua franca are transformed, localized, and re-enter the world in many languages. That circular movement—into the lingua franca and back out into other languages—is where translation lives. And it’s one of the main reasons Scott argued that translation is not just an add-on to science, but part of science itself.

A brief history of lingua francas in science

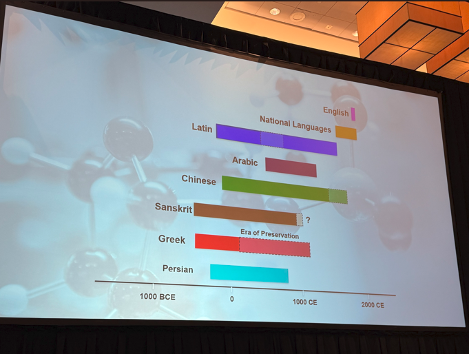

Scott took us on a quick tour through 3,000 years of intellectual history. Over time, several major lingua francas have played a dominant role in scholarship and science: Greek, Sanskrit, Persian, Latin, Chinese, and Arabic. Then follows a period with no single lingua franca but a patchwork of European national languages, until English rose to dominance.

Arabic, for example, once functioned as the scientific lingua franca across the Islamic world. Travelogues like those of Ibn Battuta in the 14th century were written in Arabic and circulated widely, connecting scholars and readers over enormous distances.

Two key lessons from this history are:

- Lingua francas last a long time. They don’t appear and disappear quickly; they shape centuries of scientific and scholarly work.

- English as a lingua franca has only just begun.

How English became the language of science

English did not become the global language of science by accident. Scott pointed to two major historical drivers:

- The British Empire, which spread English across large parts of the world.

- The United States’ scientific leadership in the 20th century, especially after World War II.

In the decade leading up to World War II, and during the war itself, scientific expertise in Europe was disrupted or destroyed, creating a large migration of researchers who mainly went to the US. Together with the lack of wartime damage, this helped the US become a key center for research and development. After the war, American institutions, funding, and infrastructure helped anchor English as the primary language of scientific publication and collaboration.

Today, English is not just one language among many in science—it is the bridge language that allows researchers worldwide to collaborate, participate in international conferences, and have access to greatest volume of contemporary science. To illustrate just how globalized science has become, Scott shared visualizations of international research collaboration. One map by Olivier H. Beauchesne shows collaborations between 2005 and 2011, where each international co-authorship is a line between two cities or countries.

Over the past 25 years, the number of countries involved in international collaborations has risen from about 80 to roughly 140, connecting not only traditional hubs in North America and Europe, but also growing scientific communities in Asia, Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East.

One vivid example is the discovery of the Higgs boson.The 2012 paper in Physics Letters B that announced the team’s observation of the Higgs particle listed close to 3,000 authors from 32 countries, all writing in one language. That language was English. This doesn’t mean English is “better” or “superior.” It means that it has become the common meeting ground where scientific work from many different places can be combined, compared, and built upon.

Translators are “nativizers” and recreators

Another interesting part of Scott’s talk was his look at historical translators in the 12th–13th centuries, when a huge body of scientific and philosophical knowledge moved from Arabic into Latin and then into European languages.

These translators did much more than move words from one language to another. They chose terminology that would make sense in their own traditions. They adapted ideas, sometimes reshaping them so they could be understood and discussed locally. In doing so, they essentially “nativized” science, allowing foreign ideas to take root in new soil.

Scott argued that modern translators, especially those working in scientific and technical fields, are doing something very similar today: translators help bring life into science, something machines, which do not speak, think, or truly understand, simply cannot do.

Key takeaways

Scott ended with four conclusions about lingua francas and translation:

- Lingua francas last a long time. They are not passing trends, and English is likely to remain central to science for decades to come.

- Lingua francas nourish science. Scholars must learn them to read, collaborate, and communicate across borders.

- Lingua francas don’t kill multilingualism, they feed it. More people around the globe are learning English in addition to their native languages, not instead of them.

- Lingua francas foster major eras of translation. Knowledge flows back into local languages. Once ideas have been published in English, they are translated, adapted, and discussed in other languages.

And, as Scott pointed out, today’s growing narrative that “AI is taking over,” only proves how central translation has become to our world: if translation weren’t so crucial no one would be so eager to automate it.

He also stressed that the richest scientific collaborations still grow out of human interaction, including informal hallway conversations, discussions at conferences, and long-term professional relationships.

Back to the lake

Scott closed his presentation the way he began, with the Rocky Mountain lake. Each stream represents a local or national scientific community. The lake is the shared scientific conversation, largely conducted in English. And from that lake, new streams flow out again: into textbooks, standards, manuals, popular science articles, and more, in countless languages.

As translators and interpreters, especially in scientific and technical fields, we are the ones helping to turn streams into lakes and lakes back into streams. We make it possible for knowledge to travel, to be understood, and to inspire new ideas elsewhere. In this globalized world, Scott’s message felt both humbling and energizing: scientific translation isn’t just something that happens after the fact. It is part of how science itself lives, grows, and connects the world.