by Pavitra Baxi, S&TD Blog Co-Editor

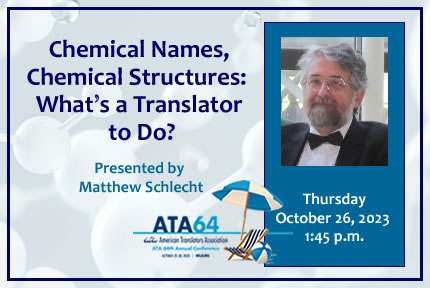

Longtime S&TD member Matthew Schlecht will be presenting at the ATA64 Conference in Miami, Florida. His session, “Chemical Names, Chemical Structures: What’s a Translator to Do?”, is scheduled for Thursday, October 26, 2023, at 1:45 pm. In this interview, Matthew gives us a peek into his professional career and a short primer of his upcoming conference session. Enjoy reading!

Pavitra Baxi: Matthew, you are well-known in the ATA circles and you are an active member of the S&TD leadership council. Could you give a brief introduction so that new members also get to know you better?

Matthew Schlecht: I am one of those people who knew from a very early age what they wanted to do in life – I wanted to become a scientist. I narrowed it down to chemistry, although briefly in the 60s I was convinced that I would explore interstellar space. Too much sci-fi in the diet! Practicality led me to double down on chemistry; I earned a doctorate and fell in love with research. Since high school, teachers had told me that I seemed to have a talent with languages, and I had studied Latin, French, Spanish, German, and later on Russian, Japanese, Chinese, and Korean. I spent six years in academia, then a total of fourteen years in research in chemistry and the life sciences, all the while using language capability to digest the non-English scientific literature. Events transpired at the mid-career point that soured me on research. As I considered what to do next, I happened to read an article on technical translation in an online language forum, and at that point my future became clarified: instead of using language in service of science and technology, I would use my science and technology background in service of providing language services. It’s been 21+ years now, and I can honestly say that I’m as happy as I’ve ever been.

PB: Before turning to translation, you had an illustrious career in the field of chemical research and technology. What made you change your mind?

MS: My academic career ended when I was denied tenure. I interviewed at a number of schools for a next position, but was part of a two-career job search and I ended up taking an industrial job as a best fit. After losing that position in a down-sizing, I joined a contract research outfit. A common negative factor in all of these postings was that I didn’t get along well with bosses, particularly those whom I did not respect. I solved the unpleasant boss problem by becoming a freelancer, and although I needed to learn business practices and how to do translation professionally (steep learning curves!), it grew into the perfect vocation for me.

PB: Most people struggle with mastering just one language in their lifetime, how did you manage to learn six languages while actively pursuing a career in chemical research and developing algorithms for chemical structures? What’s your secret?

MS: I don’t know if I have a secret. I am just highly motivated to be able to communicate through other media than the one I was born into. I also don’t mind terribly much sounding silly as I try to gain capability with other tongues because that’s how one learns. The trial-and-error approach works both for science and for language. I would hesitate to say that I have mastered all the languages mentioned above; there are four languages other than English from which I can do translation within the subject matter areas in which I am competent, and I restrict my practice narrowly to those subject matter areas. Learning science and learning languages both require a lot of time and a lot of hard work!

PB: What made you come up with the session topic “chemical names and chemical structures?”

MS: I have given a number of ATA presentations on science topics, with a focus on how those topics fit into translation work.

For this particular topic? To be honest, the inspiration came earlier this year when I had done a translation of a chemical patent and had taken care to use proper nomenclature. Then, an editor revised several of the chemical names with the comment that they were “wrong”. After an initial flush of indignation and reversing the inappropriate changes, I realized that facility with chemical names and structure might elude many translators. Some might believe that they know enough already, or that some superficial online searching might solve the problem for them. I want to address the topics of chemical names and structures to provide a starting point for translators and interpreters to understand them, and provide some resources that could be helpful to that understanding and use.

PB: What do you aim to achieve in this session?

MS: A presentation like this could easily be made far too didactic, which would be boring and unhelpful. In my mind, there are many similarities between chemistry and language, and I want to show that chemical names and structures serve the same purposes to chemists that a language does for the general population. So, I will try to present the topics in this way, that chemical names and structures are languages that can be learned and used. My aim is to offer an understanding of how these things work, and to provide tools for handling them to enable interested translators or interpreters who find this sort of content in their source material and want to be able to handle it more competently.