Over the span of my career as a professor of Germanic linguistics, the Pennsylvania Dutch language has been at the center of my research and public service. The courses I teach deal mostly with linguistic topics related to German, including regional varieties of the language. I do also teach courses related to Pennsylvania Dutch and its main speakers today, the Amish, as well as Yiddish, which shares a number of structural and sociolinguistic similarities with Pennsylvania Dutch.

At the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where I have taught since 2000, we are guided by a principle known as the Wisconsin Idea, the philosophy that what we do at the university should be of benefit to the greater community. One way I have been able to promote the Wisconsin Idea is through my affiliation with the Max Kade Institute for German American Studies (MKI), whose mission is to promote research on German-speaking migration to the Americas and to disseminate that research among scholars and the general public. The Pennsylvania Dutch Documentation Project is one of MKI’s signature initiatives.

Pennsylvania Dutch is a Germanic language spoken today almost exclusively in the United States and Canada. Its roots go back over three hundred years, to the migration of German speakers to colonial Pennsylvania. The majority of these migrants came from the Palatinate (Pfalz), hence Pennsylvania Dutch most closely resembles the dialects spoken in that region of modern Germany. However, there is nowhere in the Palatinate where one can find speakers of German who speak a dialect that is identical, or even very similar, to Pennsylvania Dutch. The dissimilarity between Palatine German and Pennsylvania Dutch is due to three major factors.

First, not all migrants to Pennsylvania from the Palatinate spoke the same dialect. There was considerable linguistic variation across the region, especially between its western (Westrich) and eastern (Vorderpfalz) subregions. Contact between different Palatine (and other) dialects spoken by the Pennsylvania Dutch founder population in the 18th century led to a levelling process that yielded linguistic output that was novel.

The second and third reasons why Pennsylvania Dutch has diverged from German in Europe have to do with the sociolinguistic situation of its speakers, and specifically the other languages they use, namely English and (standard) German. Pennsylvania Dutch people have never lived in social vacuums, meaning that they have always spoken, read, and written English. Although they saw themselves as different from their “English” (monolingual) neighbors, they identified nonetheless as Americans or Canadians, one expression of which is the use of English. The practical effect of bilingualism is that about 20% of Pennsylvania Dutch vocabulary is English-derived, a considerable number though still lower than the percentage of Lehnwörter in European German. About one-third of standard German vocabulary comes from languages like Latin, French, Greek, and, more recently, English. Beyond words outright borrowed from English into Pennsylvania Dutch, there are many examples of what linguists call calques or loan translations, word-for-word renderings from one language into another. The expression how goes it? is the calque of wie geht’s?

Here is a simple example of how Pennsylvania Dutch differs from German and Pfälzisch. Consider the following sentence: Seller Kall gleicht sei Gwicht rumschmeisse. Each one of these six words is derived from (Palatine) German, however the sentence is incomprehensible to a European German speaker from the Palatinate or anywhere else. The first word, seller, is a distal demonstrative that means ‘that’ (jener, in German). The second word, Kall, means ‘guy’ and is cognate with Kerl. The Palatine German forms of the word are Kerl and Karl, with the r lightly pronounced, while Pennsylvania Dutch Kall lacks the r entirely, a consequence of the dialect levelling I mentioned earlier. Gleicht, is the 3sg form of the verb gleiche, whose meaning is not ‘to be like, resemble, equal’, as in Palatine and standard German, but ‘to like’, a semantic shift due to the influence of English. Ich gleich dich is how you say ‘I like you’ in Pennsylvania Dutch. The last part of the sentence, sei Gwicht rumschmeisse, means ‘to throw his weight around’, a verbatim translation of the American English idiom. Put this all together, and the sentence means ‘That guy likes to throw his weight around’ and definitely not Jener Kerl gleicht sein Gewicht herumzuschmeißen.

Regarding German and the Pennsylvania Dutch, for generations and still today among the Amish and Old Order Mennonites, many speakers learned to read a form of standard German (Hochdeitsch), mostly in religious texts. However, very few Pennsylvania Dutch people ever learned to speak German or write original compositions in it. In German-speaking Europe, especially since the 19th century, the relationship between the standard language and vernacular forms of German is very different. Standard German in Central Europe is a Dachsprache that has influenced all regional varieties (dialects and regiolects) and in some cases, especially in northern Germany, replaced them entirely. On this side of the pond, there are almost no words borrowed from standard German into Pennsylvania Dutch and zero grammatical influence.

Looping back to me, forty years ago I began attending Amish and Old Order Mennonite worship services and became immersed in Pennsylvania Dutch. It was not too difficult for me to pick up the language since I was already proficient in German and trained in German linguistics, with a focus on dialectology. I eventually lived in an Amish community for several years and was baptized in a Mennonite church, which is my formal church affiliation today. I speak the two main varieties of Pennsylvania Dutch, Midwestern Amish and Lancaster Amish and Mennonite.

Several years ago, Plain people (the general term to describe Amish and traditional Mennonites) began asking me to help them out in interactions with outsiders. This has led me to serve as an interpreter in medical and legal settings, as well as in forensic interviews. Not a week goes by now that I am not fielding calls from people asking for assistance of all kinds. When I am not teaching (and the Wisconsin roads are not icy or snowy), I am often in the home or at the bedside of a Plain person in need. When I was in graduate school, I never anticipated I would one day be helping to change the burdock leaf dressing of an injured eight-year-old while comforting him in his heart language. But here I am.

Because all Plain adults are bilingual in English and Pennsylvania Dutch (or another German-related language … that’s a story for another blog post), it is tempting for outsiders to assume that they do not require interpretation or translation services. While that is true in some situations, the fact that even English monolingual speakers have difficulty understanding the language of say, healthcare or the legal system, underscores the need for help with communication in formal settings. In my work as an interpreter, I find myself unconsciously going from technical English to basic or simple English, and then rendering that into Pennsylvania Dutch. But then, as all translators know, what we produce needs to be culturally appropriate. For example, there is a word in Pennsylvania Dutch for ‘pregnant’, which is the same in German, schwanger. However, no Plain person ever uses it, for cultural reasons, preferring instead more indirect expressions like an eckschpeckte sei (‘to be expecting’).

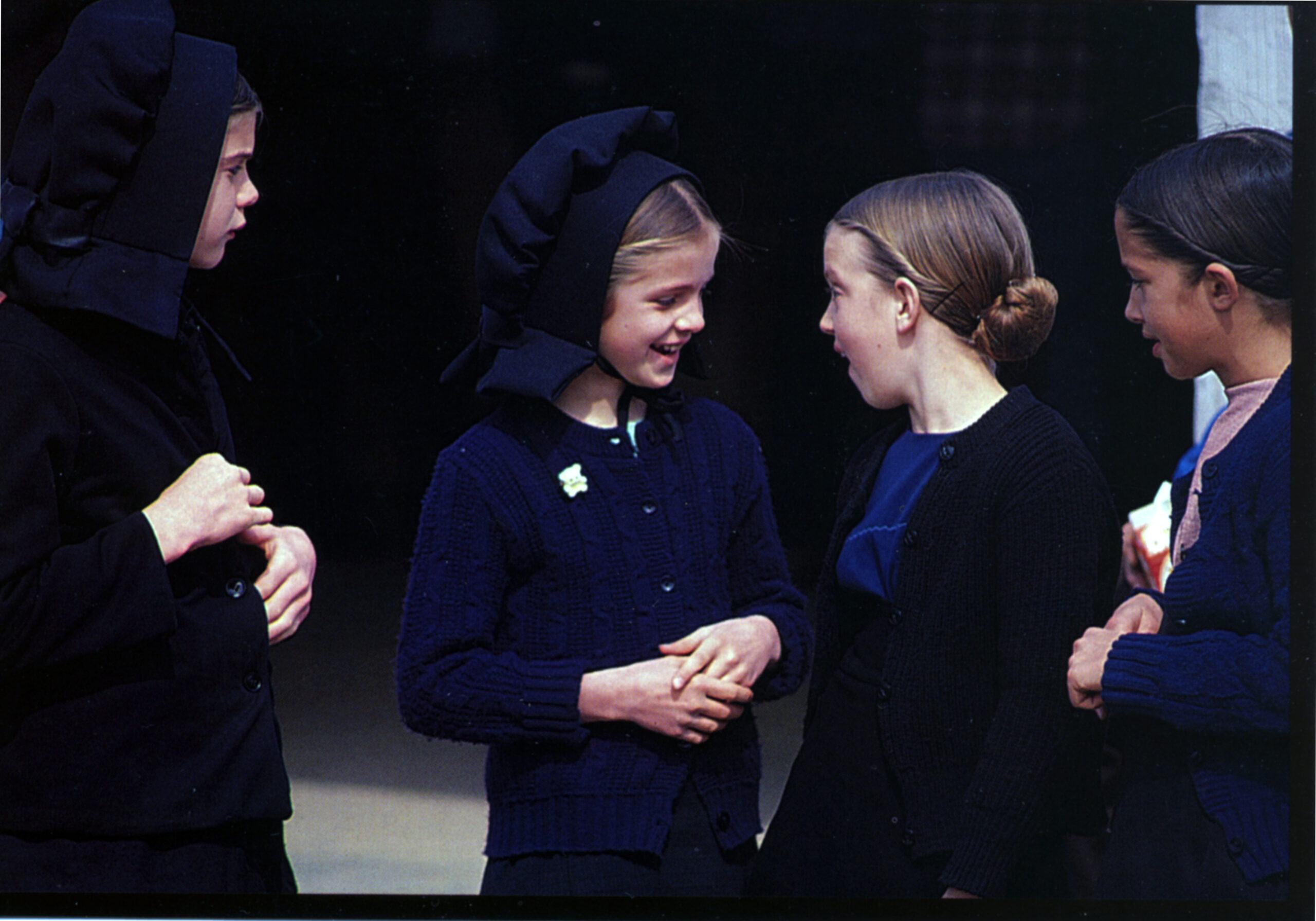

Plain groups are currently experiencing exponential growth. Their numbers are doubling every twenty years, which means that their interactions with “the English” will only increase, as will the need for culturally sensitive interpreters and translators to serve them.

- [Click here to see more details on the upcoming GLD Pennsylvania Dutch Day in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, on Saturday, July 19, 2025, which will feature Professor Louden as the keynote speaker.]

- [Click here to get more details on Professor Louden’s book, Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language.]

Mark L. Louden, Ph.D., is the Alfred L. Shoemaker, J. William Frey, and Don Yoder Professor of Germanic Linguistics and director of the Max Kade Institute for German American Studies at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. He received his undergraduate and graduate education at Cornell University and taught for 12 years at the University of Texas at Austin before joining the UW–Madison faculty in 2000. A Mennonite speaker of Pennsylvania Dutch, most of his research deals with the language and culture of its speakers. He is the author of “Pennsylvania Dutch: The Story of an American Language,” for which he received the Dale W. Brown Book Award for Outstanding Research in Anabaptist and Pietist Studies. He serves as a medical and legal interpreter, cultural mediator, and patient navigator for Amish and traditional Mennonite communities across the US.